It seems the BSE crisis is just something Canadian cattle producers are having a tough time getting over. And now there may be even more reasons to hold back on expansion.

More than 14 years after the discovery of the first homegrown case of BSE in a cow in Alberta shook the industry to its core – resulting in lost market access and billions of dollars in losses – cautious Canadian producers are continuing to rebuild their herds slowly, ever so slowly.

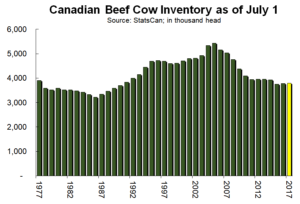

The latest livestock inventory report from Statistics Canada (released Aug. 18) provided the latest proof of that, pegging the total number of cattle on Canadian farms as of July 1 at 12.95 million, up a mere 0.1% from a year earlier. Indeed, Canadian cattle numbers as of July 1 have remained basically unchanged for the past three years, hovering about 23% below the peak level of 16.8 million head, recorded in July, 2005, in the aftermath of the BSE crisis which closed a number of Canada’s key beef export markets.

So even with the boom of three to four years ago, when everything from calves to feeders to fed cattle experienced record-high prices, Canadian producers have largely remained unmoved.

In contrast, U.S. cattle inventory reports have shown annual increases of between 2-3% over the last couple of years.

In fact, the latest U.S. inventory report, released last month, pegged the American herd as of July 1, 2017 at roughly 103 million head, a sizable 4% increase from the same date in 2015. (The July 2016 cattle inventory report was a victim of government budget cuts).

Analyst blames BSE

As some readers may remember, our March 7 blog featured an interview with Anne Wasko, marketing analyst with Gateway Livestock in Alberta. In that article, Wasko suggested the losses incurred during the BSE crisis was one of the main factors holding producers on this side of the border back from expanding.

Rather than responding to the strong prices of 2014 by aggressively rebuilding their herd as their American counterparts did, Canadian producers have instead concentrated on trying to gain back some of the equity that was lost as a result of BSE, she said.

Now that cattle prices have come back to earth, Wasko also speculated it may still be years down the road before the Canadian herd sees any significant expansion.

Given more recent developments, we’d have to agree.

Additional factors likely to limit herd expansion

The drought that has impacted areas of southern Alberta and south-central Saskatchewan has burned up pastures and feedgrain crops alike. And just as the multi-year drought resulted in heavy herd liquidation on the southern U.S. Plains a number of years ago, Alberta and Saskatchewan are likely to see something similar – albeit on a much smaller scale.

Not only have pastures in the dry areas been ruined and hay crops decimated, but the abundant and low-priced supplies of feed barley and feed wheat that were available in the wake of last year’s overly wet growing season are a thing of the past. Producers in Western Canada will be paying more for feed this fall and winter, denting profitability.

Another limiting factor may be the uncertainty caused by the North American Free Trade Agreement renegotiations. The Trump Administration has drawn a hard line on any trade agreements it doesn’t consider beneficial to the U.S., and there may be a lot to lose on the Canadian side if any new deal crimps the flow of beef and cattle to the U.S.

Market outlook not helpful

Meanwhile, the market outlook itself may not be conducive to herd expansion either. A major price cycle peak was hit in late 2014 and early 2015 in Canada, and it may be many years before producers see market conditions as strong again.

People in the cattle business know that. And in the shadow of that great peak of the past, many of them are reluctant to invest a lot of capital in breeding stock and pasture/hay land, figuring a big pay-off is probably not in the cards any time soon.

Generational disinterest

Expansion in the ag business is often the strongest when new generations enter. In recent decades, young people in general have lacked enthusiasm for the cow-calf/ranching as a business and way of life. A lot of young people these days seem to be caught in the allure of other, less labour-intensive, more high-tech industries. Cash-crop agriculture is more enticing.

Consider that on July 1, 2000 – before the BSE crisis hit – there were almost 122,800 farms in Canada that reported having cattle and calves. Fast-forward to July 1, 2017, and that number has now dwindled to just about 74,500 – a decline of almost 40%.

In southern and central Ontario, where 50 years ago most mixed farms included at least a few beef cattle, including cows and calves, empty old silos and barns dot the landscape like tombstones representing what once prevailed but is now long gone.

Positive message in lack of expansion

If there is a positive message in the Canadian beef sector’s lack of growth, it is this: Often the best business and lifestyle opportunities are those held in low regard by the crowds.

Regardless of its size, the beef cattle business will always have a place in the mosaic of Canadian agriculture. People will want beef. And at the foundation of the beef industry stands the owner of beef cows.

By John DePutter & Dave Milne, DePutter Publishing Ltd.

Brought to you in partnership by: